The past few weeks of my cognitive science course have been…challenging, to say the least. I’m not a sciency-type person, and while I’m not learning hard core neurobiology or anything like that, my brain does not grasp some of the concepts sometimes, so it’s taken a bit to really figure out what’s going on. That being said, there are a few things I’ve learned so far.

Thing number one: Cognition and cognitive science is really, really hard. So in keeping with the trend I utilize in my own course of finding easy to understand videos, here’s a video by Crash Course explaining cognition, and why we can be really, really stupid sometimes.

Thing number two: People really, really disagree on whether or not there’s such a thing as a learning style or a multiple intelligence. Dan Willingham put out a video disproving the whole idea of multiple intelligences and learning styles. Titled “Learning Styles Don’t Exist” (I know, it’s *really* vague on what the topic is, huh?), Willingham (2008) goes into a discussion about how people only believe learning styles exist because part of the theories is true. Well, if part of the theories is true, wouldn’t it stand to reason that it’s possible that the rest of it is also true, and you’re just being obstinate or testing it wrong? I mean, maybe I’m wrong there, but I know for certain that I am much better at some things than others. I’ve mentioned in previous blog posts about Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences. One of those is mathematical/logistical. I cannot math. I’m remarkably bad at it. I can add, subtract, multiply, and, in small numbers, divide. Long division? Nope—and that’s something my 11-year-old can do. Complex math? Troublesome. Imaginary numbers like in calculus? NOPE.

That’s part of what makes teaching and learning so difficult—you may not learn the way I teach, and I teach the way I learn. That’s part of what makes teaching difficult. Which leads to thing number two: Children learn and problem solve in ways that are drastically different from adults, even when allowing for multiple intelligences and learning styles. Adults don’t really think outside the box; they’re more rigid and, in general, are inflexible in regards to taking a solution (even if it’s the wrong one), and running with it. An example: I teach U.S. History I to adults. These adults, in general, have very set thoughts and ideas and beliefs about why the American Revolution happened. In general, many of these ideas are wrong, but it’s not their fault—it’s just how we teach history to children. What that means for me as an instructor is that my students are very “inside the box” when it comes to thinking critically about the Revolution as a whole and what the catalysts for independence were. And, for the most part, they’re all incorrect, but rather than think about what’s being asked, they insist on making the evidence fit their belief. It’s called historical bias (or bad history, if you’re my thesis advisor), and almost everybody who isn’t a historian does it.

But if I try to teach that same concept to my 11-year-old, that lightbulb immediately goes off, and she gets it. Her cognitive processes are more flexible because, at 11, she hasn’t gone through the same experiences that build those preconceived notions that adults are hindered by. She may not understand the politics and the nuances of the Revolution (again, mature, but still 11), but she’ll talk about the basics of the concept, and understand it. Those rules, that logic that we’re so attached to as adults—that’s what kills adult learners. More than learning style, more than anything else—trying to rework the neural pathways of adults is like trying to tear down the Golden Gate Bridge and rebuild it in a day—it just isn’t going to happen. Adults, as a general rule, follow logic and rules more than anything else. “If I read this paper, then I’ll learn that topic.” “If I learn this topic, then I’ll pass the class.” It’s very linear, very structured. Children, on the other hand, are so much more abstract in their thinking, which means they solve problems in much different ways than adults do.

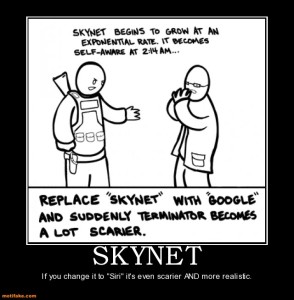

And this leads to thing number three (which might seem like it comes out of nowhere): We are absolutely screwed if artificial intelligence ever kicks off. Skynet (or the Matrix) will happen, and we will no longer be necessary. As it stands right now, AI is limited by those same rules and that same logic that adults are, and since it will be adults programming them, the AI won’t learn that there are exceptions to every rule. And then the Terminator will happen and it’ll be all over.

References

Green, H. (2014). Cognition: How Your Mind Can Amaze and Betray You. Crash Course Psychology #15. Crash Course. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R-sVnmmw6WY&index=15&list=PL8dPuuaLjXtOPRKzVLY0jJY-uHOH9KVU6

How We Learn: Synapses and Neural Pathways. (2010). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BEwg8TeipfQ

Willingham, D. T. (2008). Learning Styles Don’t Exist. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sIv9rz2NTUk